The Resilient Body

Lee-Ann Martin

The artists in Resilience resist and oppose ongoing injustices against Indigenous individuals and nations. They approach their practices with individual intents but share notions of resilience, strength and focus in the face of racism and sexism. They also share fundamental concerns: issues of government control over Indigenous cultures and the incidence of exclusion, misrepresentation and stereotypical attitudes toward Indigenous women.

Body of Work

This national exhibition by 50 Indigenous women artists is exceptional in scale and in scope. It is also exceptional in its engagement with a diverse Canadian audience — it exists outside of art galleries, in the places where people live and work and travel. Last but not least, it is exceptional in its monumentality. For too long, “big art” has been thought to be the domain of white, Western male artists. This project presents the work of Indigenous women artists writ LARGE, with significant physical presence that cannot be ignored or erased. The space is created by Indigenous women with images of self-definition and self-representation. The images insert themselves into rural and urban landscapes as a form of artistic sovereignty.

Since early colonial times, Indigenous women have been dismissed, excluded and erased. Both early European colonizers and later oppressive laws and policies imposed patriarchy upon matrilineal nations. Under the Indian Act, Indigenous women who married non-Indigenous men lost their legal rights and status as Indigenous people. These measures served to transfer political and economic power to Indigenous men who, until very recently, comprised the majority of band chiefs and councillors.

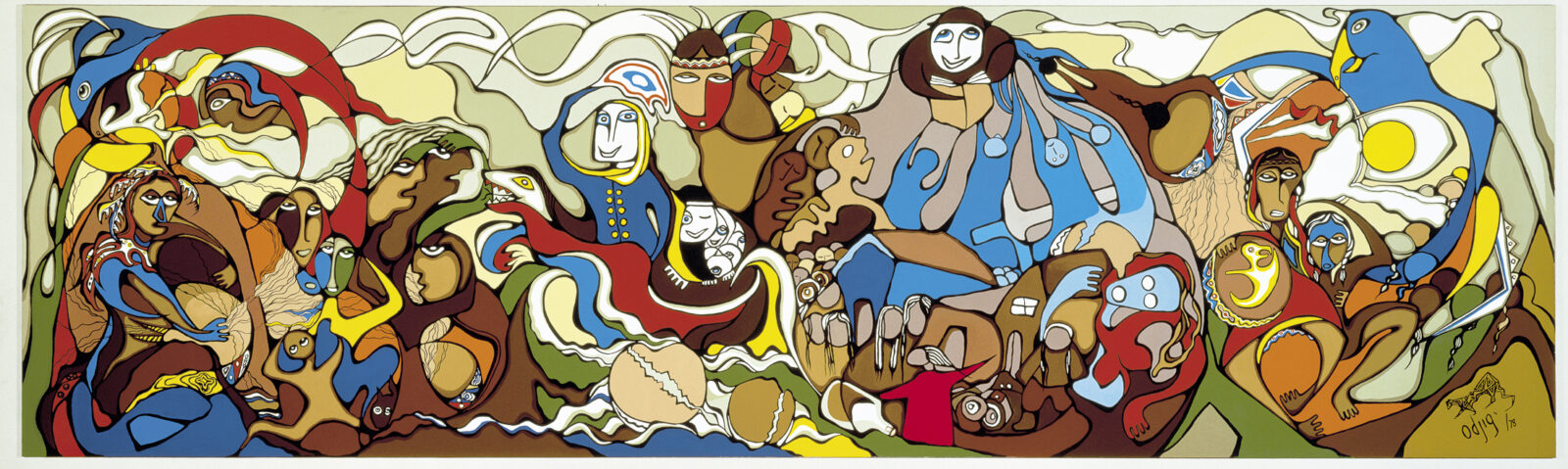

This discriminatory law also affected the federal government's support for Indigenous women artists who had lost their status through marriage. One of the most important matriarchs of contemporary Indigenous art, Daphne Odjig (1919-2016), was one of the few Indigenous women artists, if not the only one, working toward individual artistic agency as early as the 1960s. Odjig continues to inspire generations of Indigenous artists; her artistic practice and activism make a vital contribution to the ongoing revisions of Canadian art history. Odjig’s position as a respected cultural spokesperson, during a particularly vibrant and challenging period in Indigenous-Caucasian relations in Canada, forever changed the landscape within which today’s artists work. Her mural The Indian in Transition (1978) is an important treatise on this tense history.

Daphne Odjig, The Indian in Transition, 1978

However, upon her marriage in 1963 to a non-Indigenous man, Chester Beavon, Odjig lost her federally-recognized status as an "Indian" person under the Indian Act – an act that not only governs the life of Indigenous people in Canada but also defines who is, and who is not, an “Indian” in the eyes of the law. Until 1985, this act discriminated specifically against First Nations women – when a woman born with status married a non-status or non-Indigenous man, she lost her status as an Indian and was unable to regain it even if she was subsequently divorced or widowed. Furthermore, these women were financially marginalized due to their lack of federal "status.” Forcing them to live outside their communities and denying them educational opportunities, this discrimination has been identified by many as being among the root causes of violence against Indigenous women. Angered equally by the long-term effects of this discrimination and specifically by their exclusion from their own First Nations communities, in 1985 a small yet forceful group of women marched to Ottawa to demand a bill that would eliminate sexual discrimination from the Indian Act. The group included artist Shirley Bear, Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, Sandra Lovelace-Nicholas and Mary Two Axe Early. Theirs is the story of determination to end one hundred years of legislated sexual discrimination against Indigenous women in Canada. Their struggle started with the occupation of the band office on Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick, continued with a march to Ottawa, and took them to the United Nations. [i] As a result of their efforts, Bill C-31 was finally passed in June 1985, offering full reinstatement of their Indian status to affected women and, by extension, to their children, although not to their grandchildren. But the rules still favoured Indian men, who still were able to marry non-Indigenous women and pass down their status to two generations, i.e., to their children and their grandchildren.

In 2010, the federal government amended the Indian Act to extend status to one more generation (but only those born since 1985), the grandchildren of women who had regained their status through Bill C-31. [ii] In early November 2017, the federal government approved a Senate Amendment that would restore full legal status to First Nations women and their descendants born prior to 1985. This achievement came largely as a result of the dedication of two Indigenous women senators, Senator Lillian Dyck from Gordon First Nation in Saskatchewan and Senator Sandra Lovelace-Nicholas from Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick. Lovelace-Nicholas was a member of the women's group who enacted the first major amendment to end sexual discrimination in the Indian Act in 1985.

In both Canada and the United States, the federal government departments responsible for the welfare of Indigenous peoples created educational and support programs to address the "problem" of poverty and unemployment on Indigenous reserves (Canada) and reservations (United States). In the mid-1960s in Canada, the federal Department of Indian Affairs, now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), supported Indigenous male artists but withdrew support from Indigenous female artists who had lost their federal status through marriage. INAC's Art Centre only began including the works of non-status Indigenous artists in 1983, when then manager Jackson Beardy developed INAC's first official acquisition and loan agreements. [iii]

Indigenous artist and scholar Sherry Farrell Racette (also a Resilience artist) interrogates the erasure of Indigenous women artists within the context of Canadian art history. She writes:

Although issues of erasure have impacted all Indigenous people, it has been more difficult for women to emerge as individuals from the generic mass of “Indian,” “Eskimo” and “tribe.”(p.1) Recognition of Indigenous women as artists is further challenged by the categories into which their work and media primarily falls. The categories of “craft” and “ethnographic material culture” are in themselves faceless categories, further erasing women who are already faceless and nameless.(p.3) Indigenous women’s media and practices have also been relegated to either artifact (belonging to the past) or as craft (i.e., not art). While contemporary artists can challenge these categories, Indigenous women’s art history cannot avoid the realm of the anthropologist – the museum. Many art works from the historic period are in museum collections with little or no provenance, organized by object type or regional categories. These persistent generic identifications, combined with a lack of specific information, effectively erase the human maker. [iv]

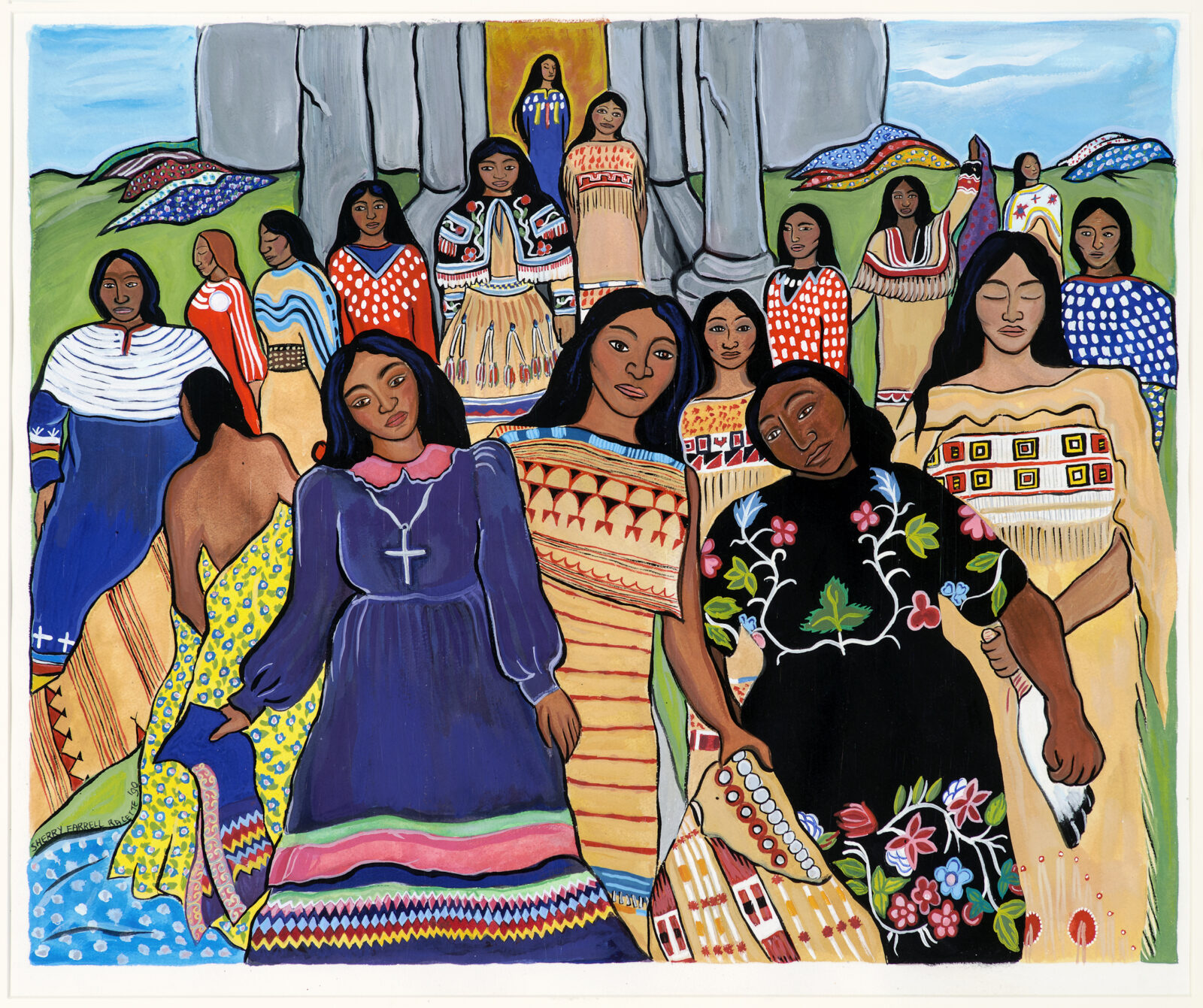

Farrell Racette has long been in the forefront of Indigenous scholarship related to the identification of Indigenous artworks and cultural material in European museum collections. In Ancestral Women Taking Back Their Dresses, she imagines that our female ancestors fly across the ocean to invade the museums and release their traditional dresses. Her painting imagines the reclamation of our rightful matrimony as the women "bring home" the dresses.

Sherry Farrell Racette, Ancestral Women Taking Back Their Dresses, 1990

Indigenous art scholar and curator Margaret Archuleta further interrogates the absence of Indigenous women artists within the male-dominated field of Native American art in the United States. Building on the seminal article by Linda Nochlin, [v] Archuleta's treatise seeks to:

... understand why Native women artists are virtually invisible in the contemporary Native art discourse as framed by the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Especially in light of the historic importance Indigenous women’s art forms have had in defining Native art and the Indian art market. [vi]

Although Canadian art institutions have progressively become more inclusive of Indigenous art than their counterparts in the United States, a cursory survey of group exhibitions throughout the 1980s across Canada reveals a similar pattern in the predominance of Indigenous male artists. Daphne Odjig was the only woman to be included with six male artists in the groundbreaking exhibition Norval Morrisseau and the Emergence of the Image Makers at the Ontario Gallery of Ontario in 1984. Notably, Odjig was the only woman of seven artists in the early collective Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., formed in Winnipeg in the early 1970s. [vii]

Beyond History, held at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1989, was an important collaboration between the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Woodland Cultural Centre on Six Nations Reserve, Brantford, Ontario. However, of the total of eleven artists, only two women artists were included, Jane Ash Poitras and Joane Cardinal-Schubert.

Throughout this period, there were many solo exhibitions by men but few by women, with some exceptions. The Thunder Bay Art Gallery is notable for organizing the majority of these solo exhibitions, among them Joane Cardinal-Schubert: This is My History and Daphne Odjig: A Retrospective, both in 1985.

Even the large group exhibitions held in conjunction with 1992 anniversaries featured predominantly male artists. For example, INDIGENA: Perspectives of Indigenous People on the 500 Years included four women in the total 19 artists; Land Spirit Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada included six women in the total 18 artists; and New Territories: 350/500 Years After included 14 women in the total 44 artists. Finally, in an attempt to address the under-representation of Indigenous artists from Atlantic Canada, in 1993 the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia organized the group exhibition Pe'l A'tukwey: Let Me . . . Tell a Story; of the 17 artists, only five were women.

With an increase in both Indigenous artist-run centres and Indigenous art curators during the 1990s, women artists were increasingly included in many exhibitions. Reservation X, held at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in 1998, was exemplary: six of the seven artists were women. Since that time, a new generation of Indigenous artists have been creating evocative works, many of which are included in Resilience.

The Female Body

Since early colonial times, Indigenous women have endured numerous atrocities to their bodies and selves. Sexual objectification, discrimination, oppression and sexual and physical violence continue to plague us. Prior to colonization, most Indigenous nations in Canada were matrilineal; within their leadership roles, women were the carriers of great political, economic and social power. Today, the mainstream media continue to marginalize the women even after their death, by emphasizing their portrayals as sex-trade workers and thus stereotyping Indigenous women as degenerate. [viii]

Many Resilience artists employ photography to critique historical and stereotypical (mis)representations of Indigenous women. Indeed, until a few decades ago, photography and Indigenous Nations had an uneasy relationship. At the turn of the 20th century, documentary photographs by predominantly male Caucasian anthropologists, government officials, artists and others contributed to the romantic falsehood of a “vanishing race.” As Rosalie Favell says:

There's a whole history, a whole legacy of Native people being photographed by others, and some of it has been a painful history. I think my generation has started turning the camera around and being the ones holding the camera and imaging our own people. [ix]

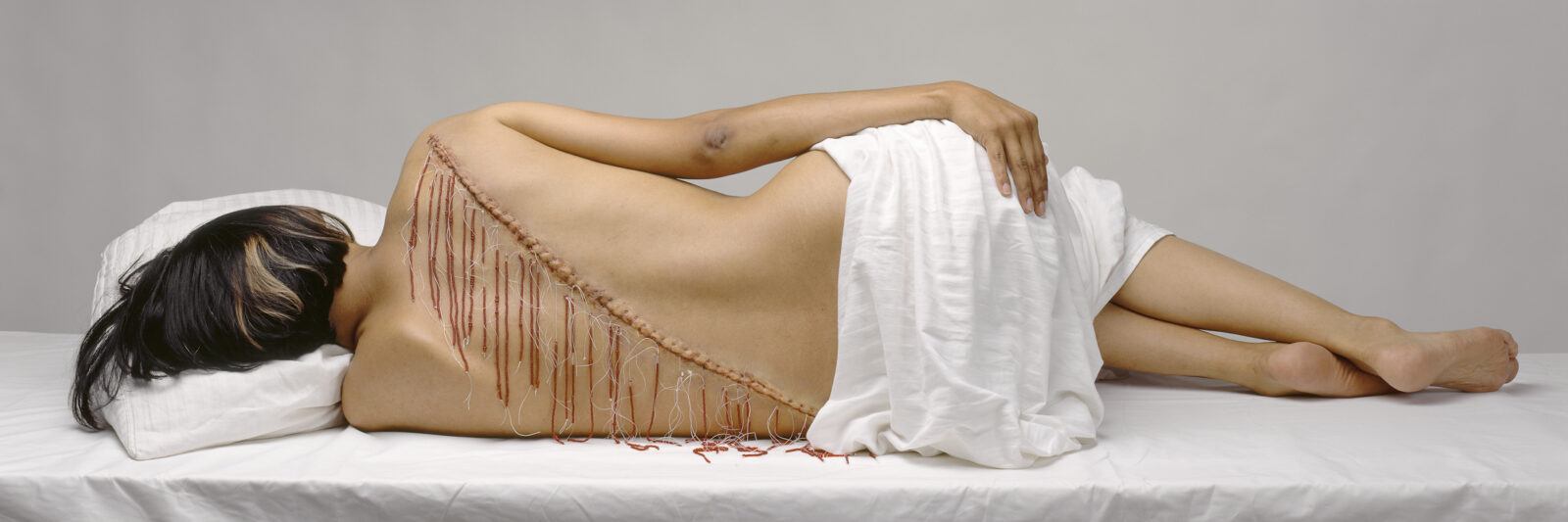

Two iconic photographs contrast notions of the reclining bodies of Indigenous women, bringing resonance to complex issues of identity and resilience. With Fringe, Rebecca Belmore poses the recumbent figure of a woman lying on a bed of white fabric with her back turned to the camera. While she is seemingly seductive from a distance, upon closer viewing, a long scar can be seen running diagonally across her back. Suggesting both beauty and trauma, beads hang down from the wound in a pattern similar to the fringe of a buckskin jacket. The careful stitching intimates something other than violence, however – a careful reparation or mending, as it references the craft of beadwork in the Anishinabe tradition. [x] As Belmore states:

She will turn her back on the atrocities inflicted upon her body and find resilience in the future. The Indigenous female body is the politicized body, the historical body. It's the body that doesn't disappear.

Rebecca Belmore, Fringe, 2008

In contrast, Shelley NIro’s mother, June Chiquita Doxtater, poses for her in her photograph The Rebel. Dressed in casual attire and reclining awkwardly yet playfully on the hood of a Rebel automobile, June smiles as seductively as possible at her daughter. Niro’s jocular, celebratory portrait captures June's femininity and the humour inherent in Indigenous cultures today, while eloquently expressing her mother's confidence in her own identity.

Shelley Niro, The Rebel, shot in 1982, shown in 1989

At the intersection of gender and sexuality, Dayna Danger's photograph Adrienne is part of her larger series entitled Big 'Uns. In the series, she equates the sexual objectification of Indigenous women and the violence directed at them with the violent and oppressive language associated with sport hunting. In this case, she cites the common term "Big 'Uns" used to refer to an animal's antlers. Danger notes that even though antlers come from a male animal, they are fetishized as if they were female breasts, in particular, “big ones.” As she reclaims power over female sexualities, the tension generated in this work by the antlers alludes to the many factors that define the sexualities of women-identified, trans, trans* and non-binary individuals.

Dayna Danger, Big'Uns – Adrienne, 2017

Indigenicity: The Urban Experience

Resilience is demonstrated in artworks that speak to ongoing racial tensions with non-Indigenous cultures, often in urban centres. According to recent census data, well over half of the country's Indigenous population resides in Canadian cities. Cities with the largest Indigenous populations in 2016 were Winnipeg (92,810), Edmonton (76,205), Vancouver (61,455), Toronto (46,315), Calgary (41,645), Ottawa-Gatineau (38,115), Montreal (34,745), Saskatoon (31,350) and Regina (21,650). [xi] Increasingly, Indigenous people have moved from their home communities to cities for economic, social, medical and educational reasons. Today, with the growing number of younger people born in cities, there has been a great growth in the number of service organizations, including arts organizations, that address the needs of this population. However, very frequently, tense relationships between urban Indigenous people and Caucasian residents bring physical and emotional harm to Indigenous men, women and children.

KC Adams and Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter address the multitude of conflicting destructive layers associated with living in the city, from racism and violence perpetrated by non-Indigenous residents to individual feelings of isolation and loneliness. KC Adams’ Perception: Leona Star is part of a series that tackles this racial rupture in the city with the largest Indigenous population in Canada. Tired of the many negative and derogatory remarks directed at Indigenous people in Winnipeg, the artist created a body of work that documents another perspective to combat these racist stereotypes. Adams’ photographic portraits unmask the real people behind the racist labels, challenging viewers to see the true diverse identities of Indigenous peoples instead of resorting to such one-dimensional racial epithets as “squaws,” "victims" and “government mooches.” Adams' images are intended to create a subtle shift away from these "perceived realities" to allow for an understanding of individual truths.

KC Adams, Perception Leona Star, 2014

Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter is an emerging Inuk artist born in Yellowknife and currently based in Calgary/Banff. She grew up in Edmonton where, according to the 2016 Census, Inuit number less than 0.01% of the population. [xii] Her work That's a-mori addresses her feelings of isolation and disconnection from her cultural practices. Drawing on the medieval Christian theory of the memento mori as it relates to reflections on mortality, she chooses to use her ghost-self as a proxy to speak to and define her own cultural disconnection. Her covered body becomes a metaphor for her own invisibility. As a young person, Nasogaluak Carpenter seeks to shape her own distinct identity as an urban Inuk while questioning the invisibility of Inuit people in the city.

Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter, (That’s A-Mori), 2016

Cities are also Indigenous territories – Indigeneity cannot be confined only to a stereotypical association with the natural environment. Nadya Kwandibens celebrates the contributions of Indigenous women in the city of Vancouver. Her photograph from the Concrete Indians series, entitled 10 Indigenous Lawyers, attests to the strength of large and small urban communities through shared values and beliefs. Kwandibens revokes the many devastating perceptions of Indigenous women who live in urban centres as she asserts the strength of Indigenous culture and identity, through resurgent acts of resistance and by reclaiming Indigenous space(s).

Nadya Kwandibens, Concrete Indians - 10 Indigenous Lawyers, 2012

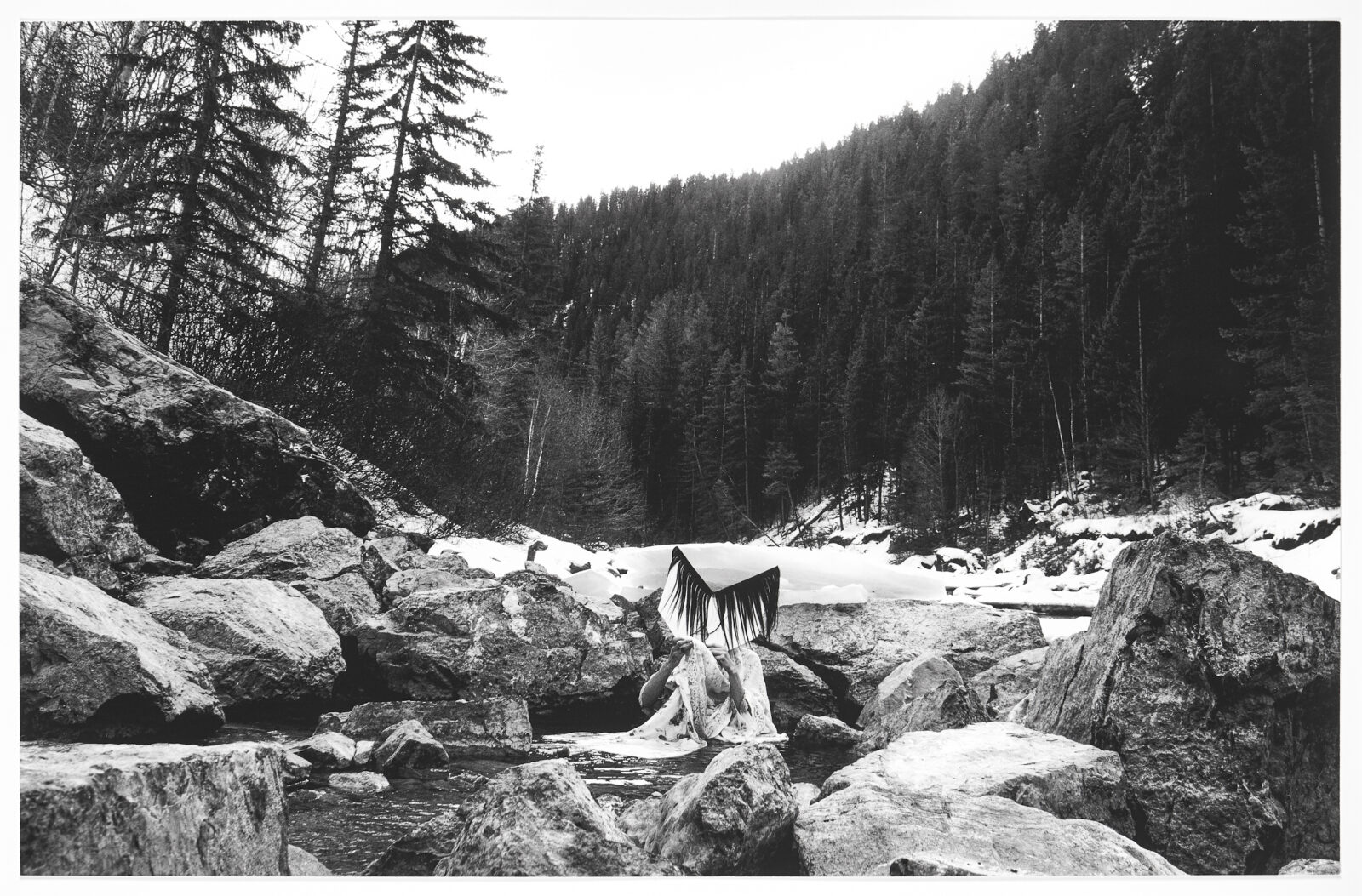

While the cities boast an increasing number of Indigenous people, many of them still maintain close connections to their home communities. In White Swan, Jeneen Frei Njootli expands on the limited notions of Indigenous spaces beyond the two-world binary so common to descriptions of Indigenous realities today. Njootli asserts that "Navigating the spaces between large cities and my home community in the Arctic serves as a foundation for my practice." [xiii]

Jeneen Frei Njootli, White Swan, 2013

In Waaschign, Maria Hupfield emplaces herself within the city of New York while holding a "mirror" painting of her home territory on Georgian Bay, Ontario. Like Jeneen Frei Njootli, she seeks to expand on the limited notions of the two-world binary to negotiate spaces for Indigenous women across the globe today.

Maria Hupfield, Waaschign, 2017

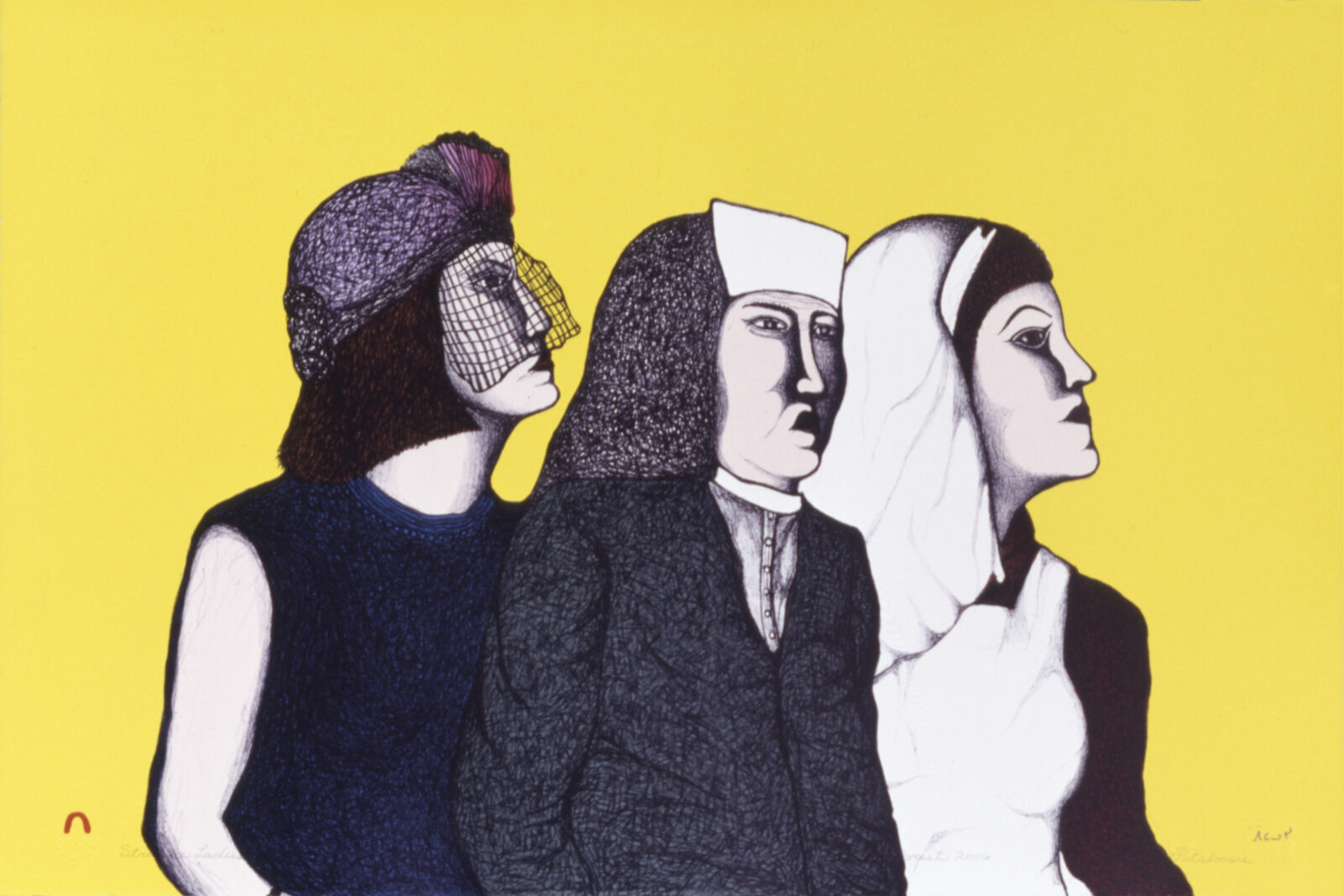

Pitaloosie Saila's Strange Ladies depicts several Caucasian women she encountered for the first time during various trips to southern cities in the 1950s for treatment of tuberculosis. A fashionable woman in Montreal wearing a hat with a mesh veil made a lasting impression. "I'd never seen anyone dressed like that before... I’d never seen a nun before either, and I remember her because she was very stern. The nurse took care of me for a time in Halifax." [xiv]

Pitaloosie Saila, Strange Ladies, 2006

In Baby Girlz Gotta Mustang, Dana Claxton confronts the uninformed and limiting misconceptions and misrepresentations regarding Indigenous people. Here, twin girls in red dresses and mukluks trimmed with rabbit fur sit on red Mustang low-rider bicycles. Their clothing reflects a combination of urban and traditional Indigenous influences, suggesting the adaptability of Indigenous cultures and thus their enduring resilience. As Rosalie Favell remarks about many of today’s Indigenous photo-based practices, Claxton's staged portraits directly confront the legacy of alterity invoked in the troubling history of photographing Indigenous peoples through the colonial lens.

Dana Claxton, Baby Girlz Gotta Mustang (Edition of 4, 2 artist’s proofs), 2008

Picturing Ourselves

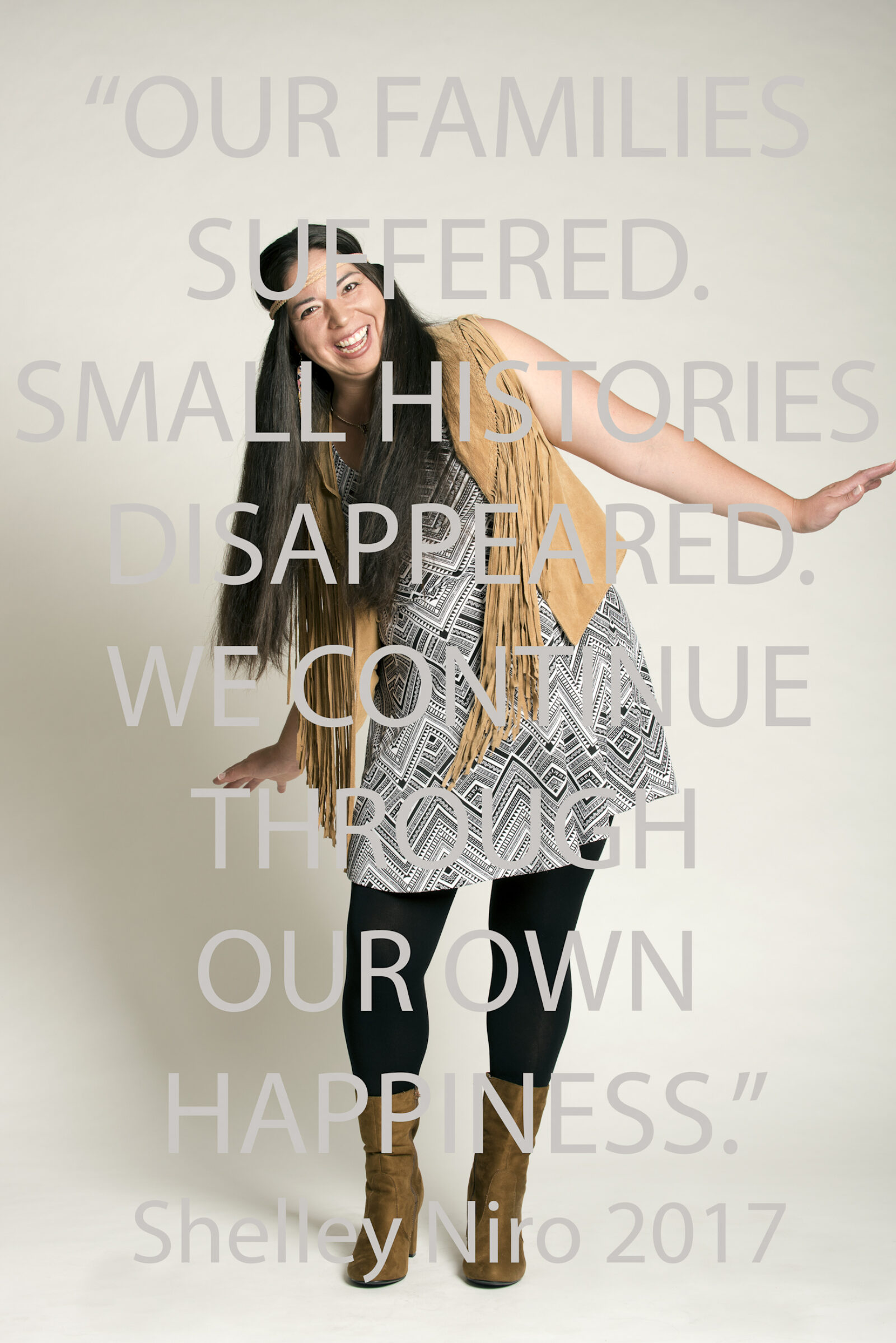

As Rosalie Favell also notes, her generation of Indigenous artists broke out of the anthropological prison of historical photographic practices to begin "holding the camera and imaging our own people." Several artists in this exhibition turn the lens on themselves in an effort to both correct history and imagine new realities. Ursula Johnson creates a self-portrait in the style of "high-fashion” photography wearing culturally appropriated clothing from hipster mall stores. Her series of four photographs, Between My Body and Their Words, speaks to the continuing practice of exoticizing and romanticizing Indigenous female bodies. In this billboard image, her playful subject wears an imitation hide fringed vest over an Indigenous-patterned dress. Superimposed on this "cute" portrait are Shelley Niro's words: "Our families suffered. Small histories disappeared. We continue through our own happiness." And so, resilience must continue in the face of this current wave of disrespect and ignorance in popular culture.

Ursula Johnson, Between My Body and Their Words, 2017

Draped in blood-red velvet cloth, standing atop boulders, Lori Blondeau's body becomes a metaphor for the resilience of Indigenous cultures in her self-portrait Asiniy Iskwew ("Rock Woman" in Cree). She laments the demolition of Mistaseni — a 400-tonne sacred boulder marking an important Indigenous gathering place that the Saskatchewan government dynamited in 1966 to make room for a man-made lake. At the same time, Blondeau pays homage to these ancient sites and their place in Plains Indigenous oral histories.

Lori Blondeau, Asiniy Iskwew, 2016

Meryl McMaster takes her performative-based self-portraits in a slightly different direction. She clothes herself in "sculptural garments" to stage her wilderness experiences, seemingly at a remove from populated centres. In Dreamcatcher, McMaster locates herself in a fanciful dream-like world where imaginary creatures act as guides for both the artist and the viewers.

Meryl McMaster, Dream Catcher, 2015

Métis leader Louis Riel was the founder of the province of Manitoba and a leader of the Métis people who lived in the Red River Settlement and across the Canadian Prairies. Many Métis artists are encouraged by a prophecy attributed to Riel: "My people will sleep for one hundred years, but when they awake, it will be the artists who give them their spirit back." While this prediction is often cited by Métis artists and organizations, the source of the foundational quotation remains unknown.

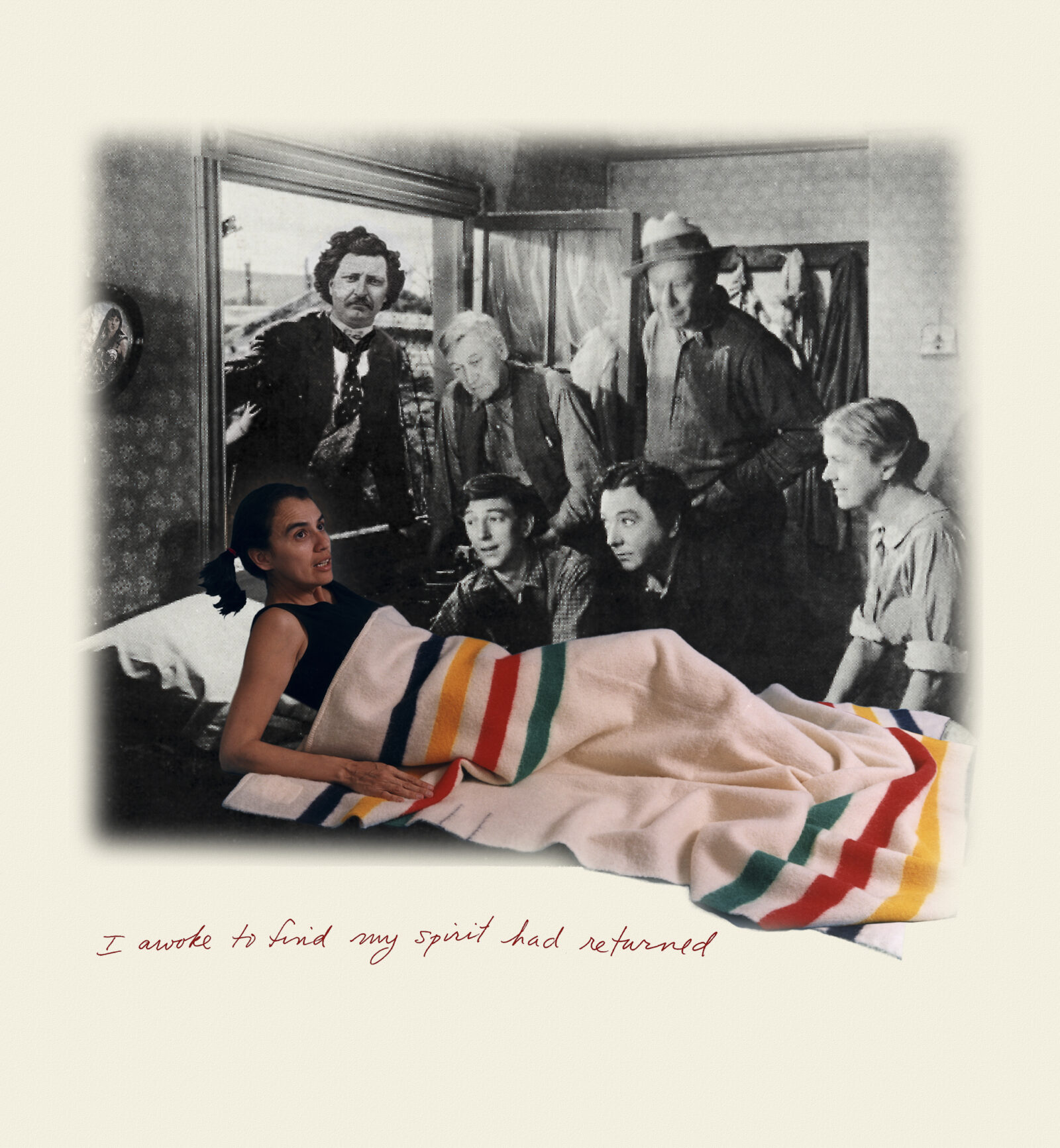

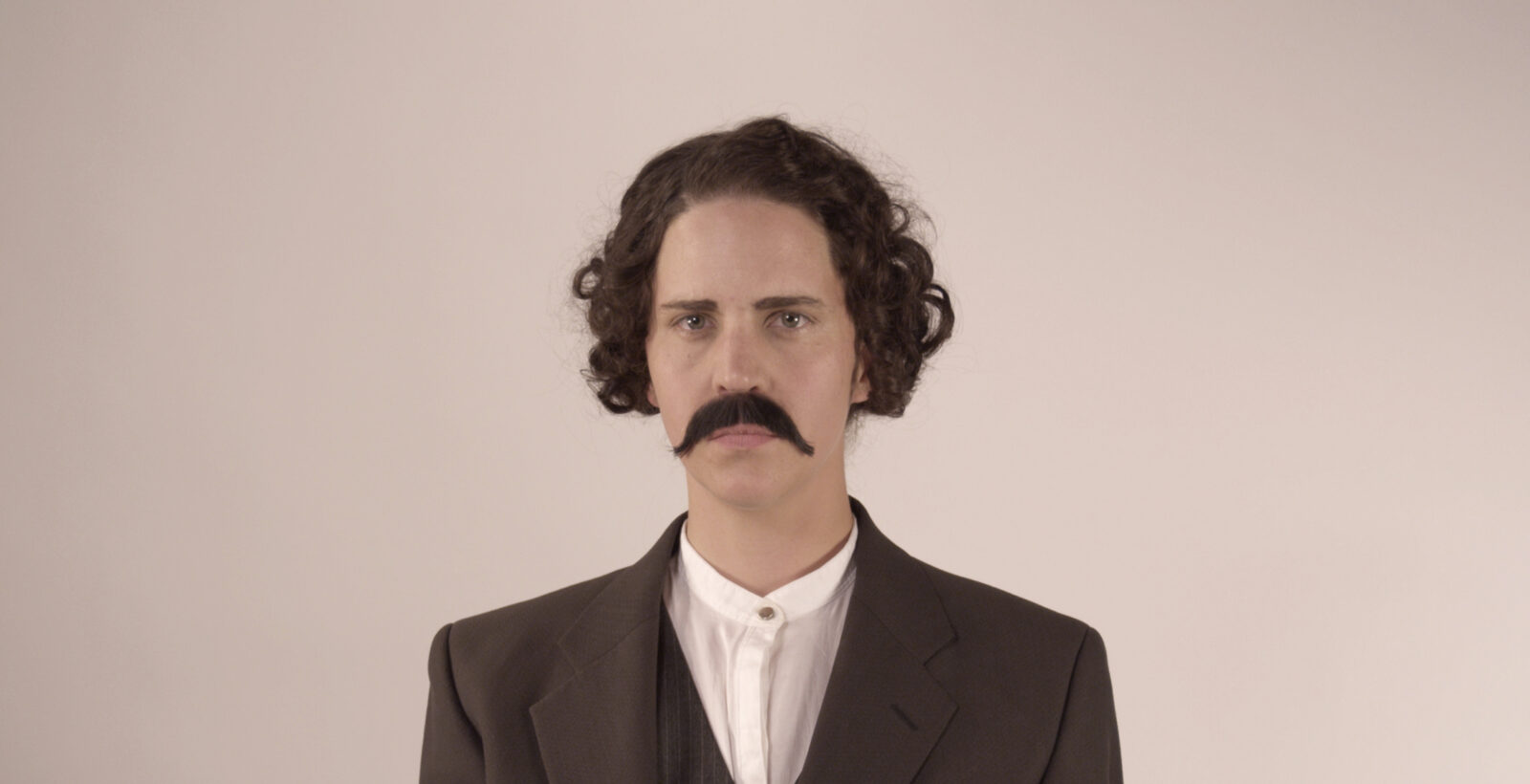

Both Rosalie Favell and Jessie Short reference Riel's iconic quotation.

Rosalie Favell, I awoke to find my spirit had returned, 1999

Jessie Short, Wake Up!, 2015

In Rosalie Favell's fantasy photograph I awoke to find my spirit had returned, the artist acknowledges the validity of Riel's prediction under his watchful eye. Emphasizing the fluidity of Métis experience, Favell replaces Dorothy in her bed, surrounded by figures from the popular film The Wizard of Oz. The fluidity of identities and cultures and the importance of Riel's prophecy also inform Jessie Short’s work in her video installation Wake Up! Transformed to resemble and, in fact, inhabit Riel, Short re-examines his iconic stature in an effort to locate herself, as a woman, in the contemporary Métis cultural milieu.

Body of Land/Water

Stewardship of the land, respect for the natural world and adaptation to change are values that have always characterized the resilience of Indigenous cultures. For Lianne Charlie, We Are the Land epitomizes the timeless connections between Indigenous people and the land, past, present and into the future. Here, Charlie depicts a Northern Tutchone woman whose moccasins root her and her baby to their ancestral homelands in Northern Canada. Lines extend from her feet into infinity, connecting her to all those who came before her and all those who will come after.

Lianne Marie Leda Charlie, We are the Land, 2015

For Joane Cardinal-Schubert and Hannah Claus, identity and memory are embodied in the land of their home territory. Moonlight Sonata becomes a metaphor for the Creator's performance in composing the large-scale universe that we inhabit. The sacred buffalo of the Plains are at one with the land and its people.

Joane Cardinal-Schubert, Moonlight Sonata, 1988

Filmed at her grandfather's community of Tyendinaga, Hannah Claus' repeat along the border carries the essence of community, as white forms from the beadwork on a woman's legging become "embeaded" on the land.

Hannah Claus, repeat along the border, 2006

Indigenous cultures across the country – and across the globe – connect with their natural world as Mother Earth. The feminine appellation inspires a special relationship with the earth that involves respect and reciprocity. In her Mother Earth, Jackie Traverse depicts a generous Mother who offers gifts of sweetgrass with which we can offer up our prayers.

Jackie Traverse, Harvesting the Hair of Mother Earth, 2019

Sonia Robertson's installation Dialogue etre elle et moi à propos de l'esprit des animaux expresses a poignant conversation between the artist and her late sister, Diane. The bones and furs honour the relationship between their family's fur business in Mashteuiatsch, Quebec and the animal spirits of the land.

Sonia Robertson, Dialogue between her and me about the spirit of animals, 2002

Nigit'stil Norbert's poignant photographs from her Reflect series offer a personalized interpretation of the urban environment of Toronto. Her abstracted images of stray fragments of trees and water, moonlight, sunlight and sky eliminate the built and human presences of the city to reveal a natural world that reflects the artist's sensibilities.

Nigit'stil Norbert, Reflect, series of 9, 2009

Patricia Deadman's body of work “has remained consistent in its use of land as a metaphor for culture and the baggage we tend to carry with us in our daily lives." [xv] Against the atmospheric panorama of the mountains and sky in Glacier National Park, British Columbia, Beyond the Mist reflects the artist's meditations on history and place. While in residence at the A.O. Wheeler Hut operated by the Alpine Club of Canada, she sought to connect viscerally with the sensory elements of her environment and to delve "beyond the mist." A.O. Wheeler was one of the founders of the Alpine Club; the Wheeler Hut is known as the "Birthplace of North American Alpinism." [xvi] Here, settler mountain culture and Indigenous history collide in Deadman's musings.

.jpg)

Patricia Deadman, Beyond the Mist, 2001

In the early history of the country, Canada's rivers were highways; their shorelines thus represent transition spaces and sites of encounter. For Indigenous peoples throughout Canada, these shorelines where for centuries they had camped, traded and shared information became zones of first contact with Europeans. Lisa Myers' video still, through surface tension, encompasses the shoreline and the Parliament Buildings on the Ottawa River. This image underscores the ongoing tensions between Indigenous peoples and the federal government, while at the same time giving primacy to the value of water as the centre of life.

Lisa Myers, through surface tension, 2013

Canada's newest territory, Nunavut (“our land” in Inuktitut), officially separated from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999. Kenojuak Ashevak's expansive aerial view, Nunavut: Our Land, provides a telescopic depiction of the abundance of seasonal activities and movement on the land and water in her home territory.

Kenojuak Ashevak, Nunavut - Our Land, 1992

Like many Inuit families, Shuvinai Ashoona and her family left the community of Cape Dorset in the late 1970s. Living independently in outpost camps gave the artist a close familiarity with and respect for the land. [xvii] Ashoona's Summer Sealift shows the arrival of the sealift, a crane-bearing cargo ship that makes an annual delivery of supplies to remote Arctic communities.

Shuvinai Ashoona, Summer Sealift, 2003

Most of the supplies delivered by the annual sealift in Nunavut are offered for sale in co-op stores. A community hub, the store functions both as a place to hang out and as a provider of essential supplies and services to remote northern communities. As many Inuit families moved off the land to form permanent settlements around trading posts in the early 20th century, their reliance on southern imported goods increased.

Annie Pootoogook, Cape Dorset Freezer, 2005

In Cape Dorset Freezer, Annie Pootoogook depicts the co-op store in her hometown of Cape Dorset in a light-hearted image of Northerners browsing in front of a supermarket freezer. Some of the shoppers are dressed in traditional Inuit parkas, including one woman carrying her baby in her amauti. The composition represents a common theme in Pootoogook’s art: the tension between traditional life on the land and contemporary Inuit life. Tragically, after living for nearly nine years in Ottawa, Pootoogook was found dead in Ottawa’s Rideau River in September 2016. Still, the tragic circumstances of her death cannot diminish her revolutionary impact. Inuk art historian and curator Heather Igloliorte wrote that Annie Pootoogook “challenged viewers’ expectations of igloos and dog teams and instead revealed our ‘matchbox houses’… [and] the Northern Shore with its refrigerators lined with freezer-burned frozen dinners.” [xviii] Along with her cousin Shuvinai Ashoona, Pootoogook is credited with introducing a powerful new artistic approach that offers an alternative to the traditional treatment of the Inuit experience.

Throughout the world, Indigenous Nations continue to resist abuses perpetrated by government and corporate interests that view the land and waters as little more than natural resources to be appropriated and exploited. In Canada, Indigenous communities have long led protests against numerous atrocities perpetrated on the land and water. In late 2012, four women in Saskatchewan (Sylvia McAdam, Jess Gordon, Nina Wilson and Sheelah McLean) held a meeting to educate communities on the impacts of the Canadian federal government's proposed Bill C-45. This omnibus bill called for the removal of specific protections for water and fish habitats and the improper "leasing" of First Nations territories, while it failed to consult with the Indigenous people most affected. Entitled Idle No More, this meeting:

... inspired a continent-wide movement with hundreds of thousands of people from Indigenous communities and urban centres participating in sharing sessions, protests, blockades and round dances in public spaces and on the land. [xix]

More recently, the Onaman Collective has organized various actions to call attention to the desperate need for healthy water and land. Based in Northern Ontario, the collective includes Christi Belcourt (a Resilience artist), Isaac Murdoch and Erin Konsmo. Indeed, their captivating image of Thunderbird Woman has quickly become the visual metaphor of Indigenous resistance to incursions such as the Energy East Pipeline and the Dakota Access Pipeline with No DAPL. [xx]

In Mni Wiconi - Water is Sacred, Lita Fontaine captures the energy and urgency of a protest rally inspired by the actions of the Onaman Collective in September 2016, at The Forks in Winnipeg. Thunderbird Woman figures prominently in the foreground of Fontaine's photograph. For the artist, such art and activism reaffirm the eternal connection between Indigenous peoples and the earth, elements that continue to inspire her art.

Lita Fontaine, Mni Wiconi - Water Is Sacred (The Forks, Winnipeg, Manitoba, September 18, 2016), 2016

Staged in the "managed landscape" of Banff National Park, Amy Malbeuf's own image is encased in a unitard that conceals her identity while it reveals her female body. Unbodied Rebirth unveils the inherent complexities of culture and knowledge embedded in the body of the land. Here, Malbeuf denounces the violence imposed upon the land and on ourselves - most especially upon women's bodies. She explores humanity’s dysfunctional relationship with the land and our disconnection from knowing what the land knows.

Amy Malbeuf, unbodied rebirth, 2011

In The Sun is Setting on the British Empire, Marianne Nicolson reverses the spatial relationship between the sun and the Union Jack on the current provincial flag of British Columbia. This orientation recalls the design of the flag introduced in the late 19th century, when the negotiations of early agreements were underway with Indigenous Nations in BC. The visual relationship then became reoriented in the early 20th century, such that the Union Jack and the sun were reversed. Nicolson's image reversal alludes to the popular saying "the sun never sets on the British Empire," meaning that the British Empire was once so expansive that some part of it was always in daylight. The background text in Chinook Jargon translates into English as "The Sun is Setting on the British Empire." [xxi]

Marianne Nicolson, The Sun is Setting on the British Empire, 2017

Bonnie Devine's installation Battle for the Woodlands corrects an early 19th-century map of Upper and Lower Canada to reflect an Anishinaabe worldview. Devine challenges the "official" historical accounts associated with the exploits of early colonial exploration and claiming the land. The process of bestowing European place names and denying Indigenous title and ownership exemplifies the appropriation and possession that were central to European colonial strategies. Devine's work reclaims the land and the water through Indigenous mapping and naming.

Bonnie Devine, Battle for the Woodlands (detail), 2014, 2015

Tanya Harnett laments the actions of that "invisible hand of industry" in her Scarred/Sacred Water series. Here, in Wabumum, Harnett depicts the scene of a clean-up site following a 700,000-litre oil spill at Paul First Nation in Alberta. Community members directly affected by contamination of their water supply used red food colouring to highlight the polluted area. Harnett exhorts all Canadians to share in taking responsibility for the health of the land and the water with Indigenous sovereign nations.

Tanya Harnett, Paul First Nation - 2005 Wabamum Clean-up Site of a 700,000 Litre Oil Spill (detail), 2011

In Nuliajuk in Mourning, Heather Campbell joins Tanya Harnett in lamenting the contamination of waters, this time by enormous volumes of garbage, most of it plastic. According to Ecowatch, giant garbage patches – one twice the size of Texas – can be found floating around in the oceans. (www.ecowatch.com) We are bombarded daily with news of the devastating effects of plastic pollution on creatures of the sea. Campbell wonders sadly how the Inuit sea goddess, Nuliajuk, would react to seeing one of her creatures lying dead on the beach because of this pollution.

Heather Campbell, Nuliajuk in Mourning, 2017

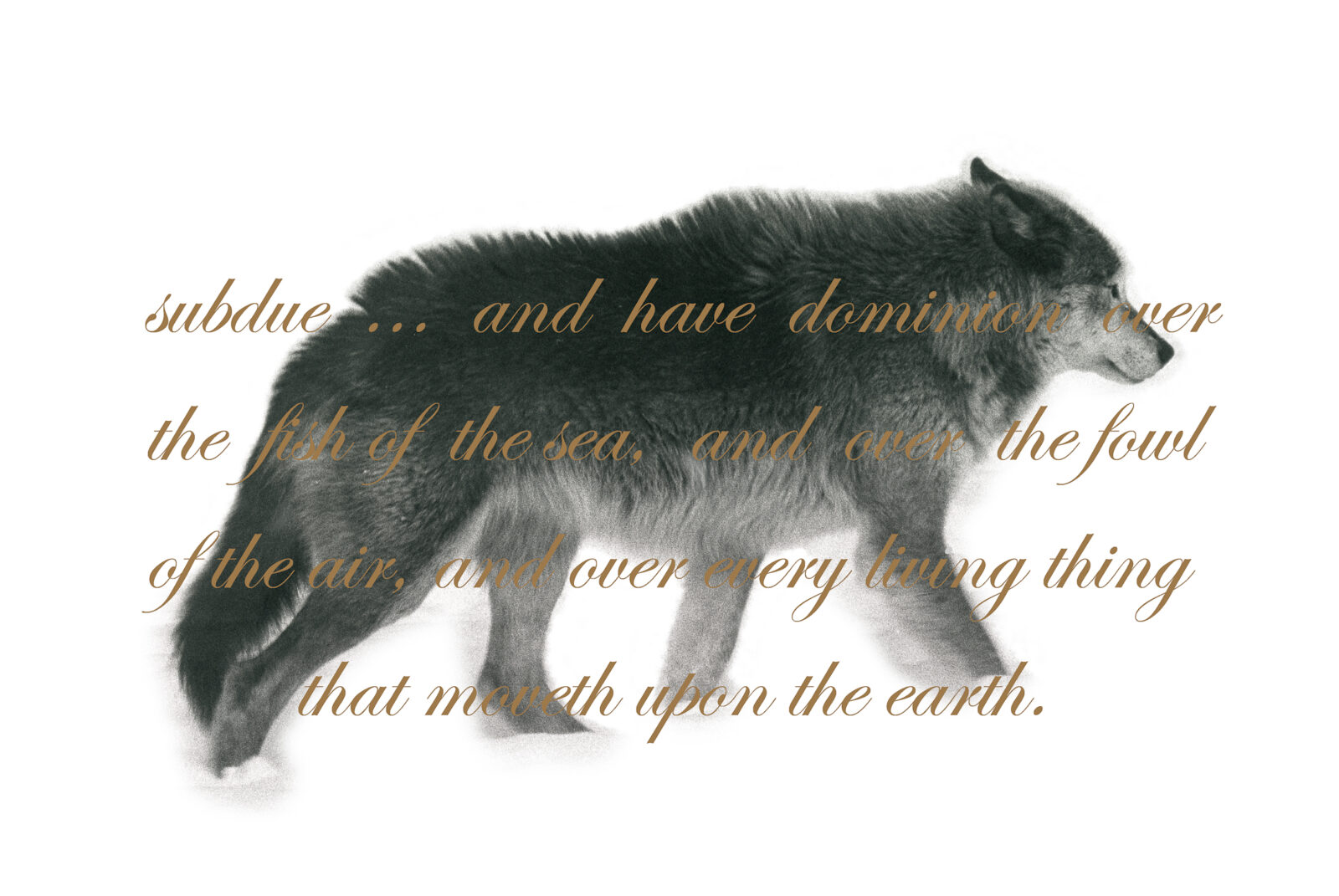

Also on this theme, Mary Anne Barkhouse invokes and interrogates notions of authority and control in Dominion. Superimposing a quote from the Book of Genesis over the photograph of an alpha-female wolf, she questions by whose authority humans have received the right to dominion over the earth and all of the animal kingdom. Here, a female wolf becomes the embodiment of the strength and resilience of Indigenous knowledge, worldviews and relationships with nature.

Mary Anne Barkhouse, Dominion, 2011

Bodies of Knowledge

Traditional, or customary, Indigenous knowledge encourages individuals and communities to move between the past and the present. While much of this knowledge is drawn from a prior time and place, it is not a landscape of the past. Ancient knowledge informs the cultural beliefs and practices of contemporary Indigenous Nations in the present day and into the future. With Deluxe, Caroline Monnet combines elements of historic Indigenous abstraction and typography in order to give primacy to the place of Indigenous women in today's cultural landscape.

Indigenous knowledge is a complex and cumulative body of knowledge that encompasses customary technologies, ecological considerations, medicines, religious practices and languages. However, since early colonial times, the knowledge, history, cultures and practices of Indigenous peoples have largely been subordinate to the official "History" of this country. Resilience artists not only celebrate and reclaim this body of knowledge but also propose critiques of the many colonial incursions that have silenced Indigenous (women's) voices.

In Mi'kmaq Universe, Teresa Marshall conveys the complexities and continuum of the six worlds within the Mi'kmaq cosmology. Marshall asserts that the cultural rupture precipitated by colonial greed and aggression has been mediated and can be shared into the future through the encoded messages and beliefs in contemporary Mi'kmaq songs, stories and artworks.

Teresa Marshall, Mi’kmaq Universe, 2005

Nitewaké:non, “the place where I come from,” expresses Melissa General's connection to the history of her homeland, the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory. Wrapping herself in a long bolt of red cloth that she had buried in the earth, General breathes in her ancestors’ knowledge of the land.

Melissa General, Nitewaké:non, 2014

Sharing the knowledge with our children and grandchildren is essential for bringing each culture forward into the future. In the photograph Nalujuk Night in Nain, Jennie Williams depicts a masked Nalujuk intended to both terrorize the community and teach lessons to the children in Northern Labrador. Held annually on January 6, Nalujuk Night, or Old Christmas Day, celebrates a Moravian/Inuit tradition. Williams' documentation of community traditions in her home of Nain creates spaces for the sharing of stories and traditional knowledge.

Jennie Williams, Nalujuk Night in Nain, Digital photograph

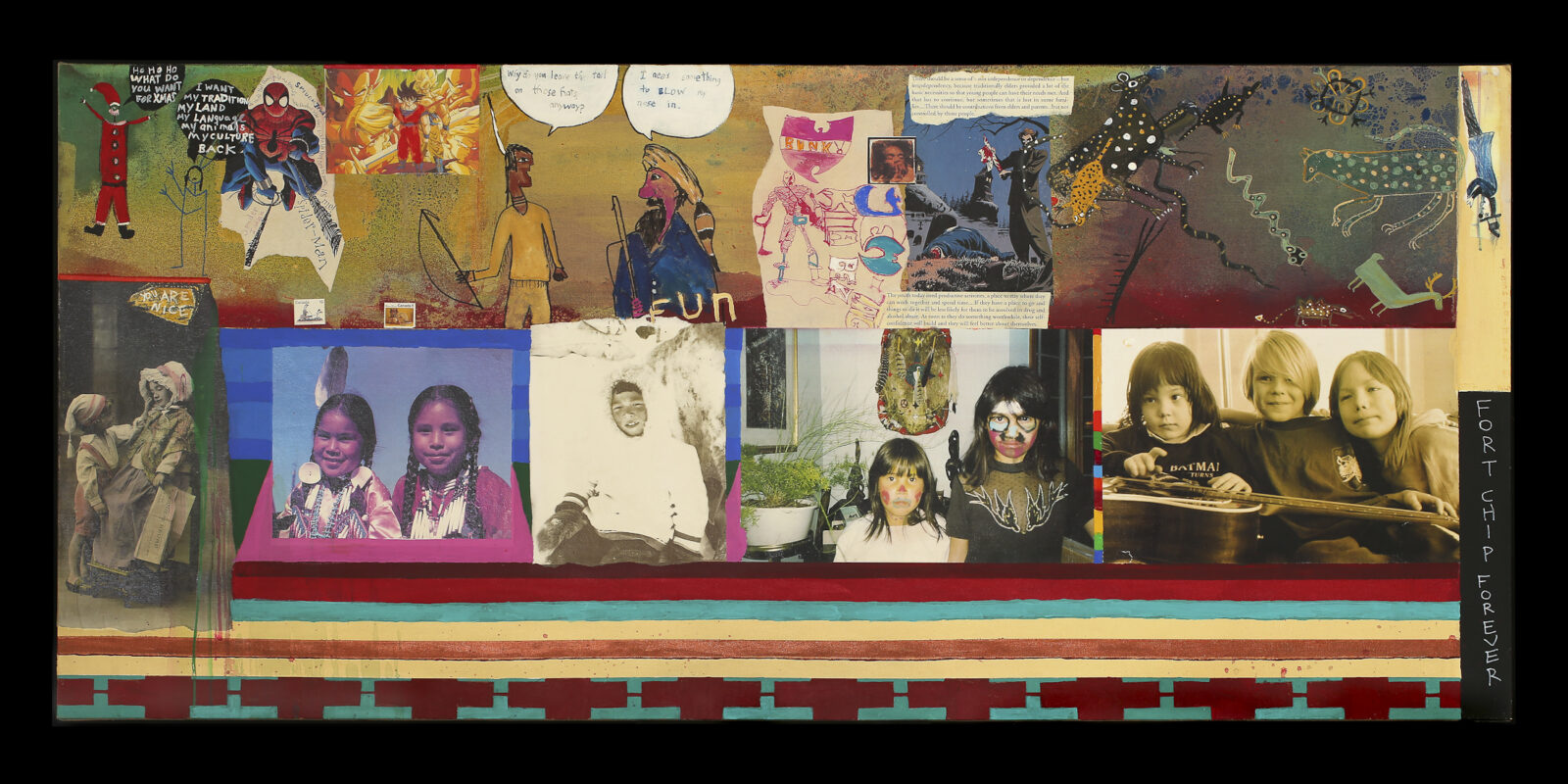

Using photographs, texts and cartoons, Jane Ash Poitras’ Fort Chip Future presents the young and smiling faces of those whose future depends upon the health of the land and respect for the treaties. Here, Poitras connects her young sons and their friends to her place of birth, the remote community of Fort Chipewyan, Alberta.

Jane Ash Poitras, Fort Chip Future, 2000

Naw Jaada/Octopus Woman by Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson challenges the persisting denial of Indigenous Title in Canada through antiquated colonial laws. Photographed as Naw Jaada, the artist reminds us that the power of the female octopus is her singular devotion to the next generation. Thus, we need to ensure that future generations commit to the health of the land and the waters of the earth.

Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson, Naw Jaada | Octopus Woman, 2017

Beginning in 1701, in what was to eventually become Canada, the British Crown entered into solemn treaties to encourage peaceful relations between First Nations and non-Indigenous settlers. In entering into these treaties, Indigenous leaders understood that they were negotiating peaceful agreements with the respective governments to share the land and to ensure their communities' survival over the next several centuries. However, the reality is that most of these treaties have been broken repeatedly or remain unresolved today. The works of Ruth Cuthand and Vanessa Dion Fletcher address the ongoing betrayal of the true spirit and intent of the treaties that launched complex, bitter struggles for territory and rights from the past into the present.

Ruth Cuthand's Treaty Dress is a composite of two recognizable flags, the Stars and Stripes of the United States and the Union Jack of Britain, also of Canada until 1967. It reminds us that in North America "We Are All Treaty People." Cuthand combines these two symbols of colonial power to metaphorically redress issues associated with treaty rights that remain outstanding throughout Canada and the United States.

Ruth Cuthand, Treaty Dress, 1986

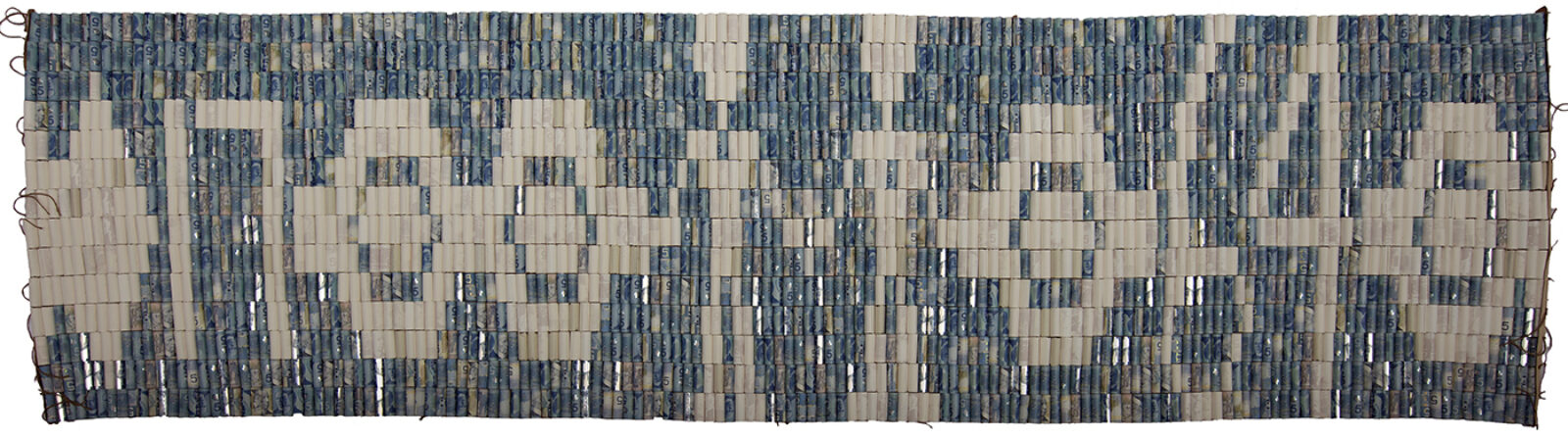

In the eastern regions of the continent, early wampum belts were created from whelk and quahog shells. These belts signified formal agreements to establish and renew relationships between nations, and they are of particular significance with regard to treaties and covenants made between Indigenous peoples and the European colonial powers. By replacing the shells in the original wampum belts with Canadian 5-dollar notes and screen prints of that note, Vanessa Dion Fletcher replicates the Western Great Lakes Covenant Chain Confederacy Wampum Belt of 1764. In so doing, Relationship or Transaction questions "the role of money in bypassing and dissolving nation-to-nation treaty relationships." [xxii]

Vanessa Dion Fletcher, Relationship or Transaction, 2014

Beadwork has long been associated with Indigenous art forms, predominantly those created by women. Imported from Europe and Asia, traded with early colonial merchants and later with the Hudson Bay Company, glass beads eventually replaced traditional elements such as porcupine quills, shells and stones used by Indigenous peoples throughout North America. By the late 19th century, Indigenous women were creating beaded items for their own use as well as to supply tourist souvenirs to a burgeoning market. In the 1800s, Métis women had begun to sell large quantities of floral beaded items to support their families. Christi Belcourt acknowledges the flower beadwork as one of the "artistic legacies left for us by our ancestors." For over 20 years, Belcourt has studied plants and the natural world to gain an understanding of the Métis culture, worldview and spirituality. In This Painting is a Mirror, she seeks to reflect back to the viewer all the beauty that is already within them.

Christi Belcourt, This Painting is a Mirror, 2012

Several Resilience artists use glass beads as a medium not only to honour this historic practice but also to comment on contemporary realities. Bev Koski beads coverings for various kinds of kitsch dolls, dolls that have become collectors' items as well as demonic presences in late 20th-century horror films. Koski's dolls are equally horrifying in their personifications and caricatures of Indigenous peoples. Whether created to promote sports team logos, Hallowe’en costumes or toys, these dolls and other derogatory misrepresentations denigrate and insult Indigenous people throughout the world. With these tiny beaded bodies, Koski seeks simultaneously to conceal and reveal these stereotypes.

Bev Koski, Ottawa #1 and Bearlin #1, 2014

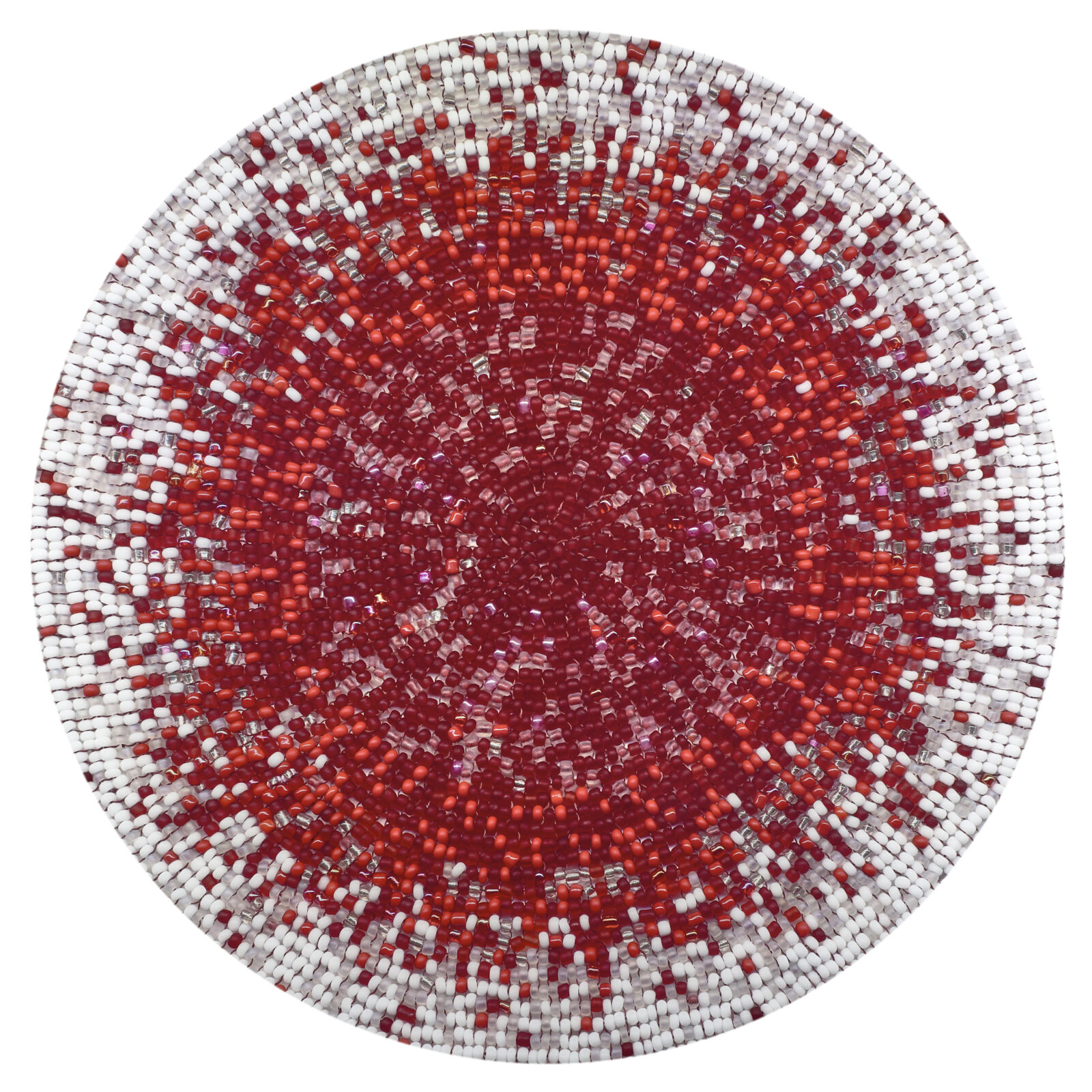

A popular phenomenon today is the proliferation of DNA ancestry testing kits that help individuals to discover insights into their ethnicity. Nadia Myre's beaded medallion Meditations on Red, #2 probes the issues surrounding Indigenous identity and "official" status through blood composition as determined by the federal government. Her beaded “portraits” reflect varying degrees of racial purity or hybridity between “red” and “white.” She highlights the ongoing debate around who can claim Indigenous identity in the eyes of the federal Indian Act, particularly Indigenous women who, until the passing of Bill C-31 in 1985, lost their status if they married a non-Indigenous person.

Nadia Myre, Meditations on Red, #2, 2013

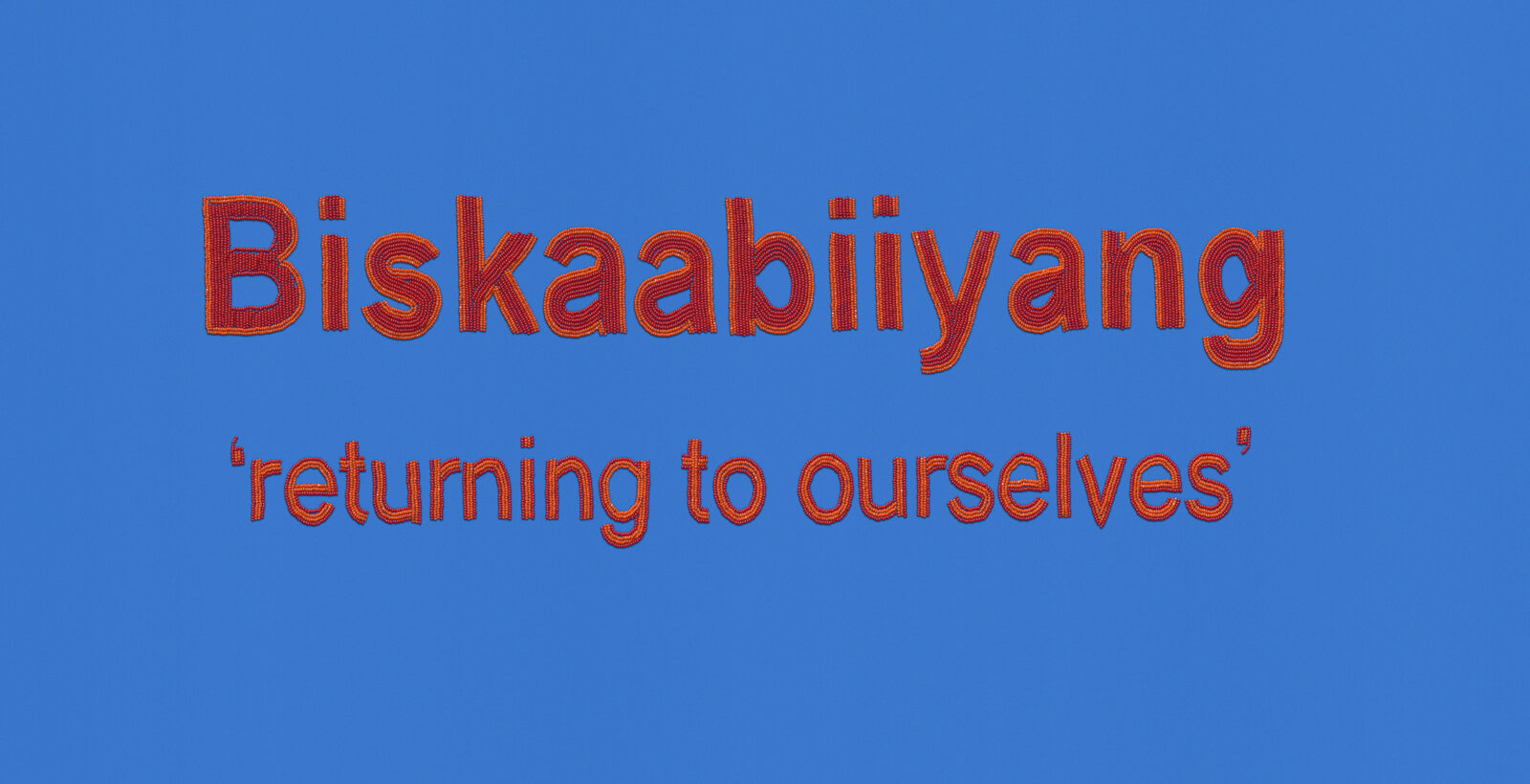

In a practice as old as beadwork itself yet contemporary in its intent, Rebecca Baird carefully applies beadwork to cloth in Biskaabiiyang – returning to ourselves. For Baird, the use of beads speaks to the enduring qualities of adaptability and resilience residing within Indigenous languages and cultures. Her text provides an example of a possible Anishinaabe interpretation of the English word "resilience."

Rebecca Gloria-Jean Baird, Biskaabiiyang – returning to ourselves, 2017

A sense of timelessness that moves the past forward into the future is embodied in Skawennati's Jingle Dancers Assembled, a production still taken during the filming of TimeTraveller™, Episode 04. In this series, the artist uses the technique of machinima, making movies entirely in a virtual environment, to present the story of Hunter, a Mohawk man who lives in the year 2121. In his journey back through history, he meets Karahkwenhawi, a young Mohawk woman from the present. Here, Karahkwenhawi finds herself surrounded by other jingle dress dancers in the year 2112 at a mega-powwow in Winnipeg. First performed in the early 20th century, the Jingle Dress Dance is associated with healing, whereby each dancer is the holder of certain spiritual knowledge. On the dancers’ regalia, multiple rows of metal cones create jingling sounds as they move. "The rhythmic sound of the jingles is said to be very beautiful, like 10,000 raindrops on a tin roof." [xxiii]

Skawennati, Jingle Dancers Assembled, 2011

Bodies of the Missing and Murdered

As I write this essay, friends, family and loved ones gathered in communities across the country to remember those who are gone and to mark the first Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Honouring and Awareness Day on October 4, 2017. In Manitoba, about 200 people gathered at the Legislature Building as the province marked the inaugural day to honour Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Nahanni Fontaine, MLA for St. Johns, introduced Bill 221 to the Manitoba government in 2016, which made Manitoba the first provincial government in Canada to have an official day to honour MMIWG. [xxiv]

In her REDress project of 2014, Jaime Black installed red dresses in locations throughout the country to evoke presence by marking absence, as a visual reminder of the staggering number of women who are no longer with us. In this untitled work from Conversations with the Land, Black's body animates one of the red dresses in a dance, re-invigorating the vitality of Indigenous women and their connectedness to the ancestral wisdom and knowledge of the land.

Jaime Black, Untitled, 2016

Mary Longman's powerful image Warrior Woman: Stop the Silence! honours the spirits of all the Indigenous men, women and children who have died for the sake of colonial land acquisition. She states that:

This work is a national call to action for the federal government to acknowledge the history of Indigenous genocide in Canada and in North America; to legislate this history as mandatory curriculum in Ministry of Education school texts; and to fund memorial sites across Canada. [xxv]

Mary Longman, Warrior Woman: Stop the Silence!, 2017 revisions of 2014 version

Although she no longer walks among us, in a real and deep sense Daphne Odjig's legacy is enduring. The works of many Indigenous women artists present individual, critical observations of the contemporary world while simultaneously revealing Indigenous identities that are layered and multi-faceted. The complexity of these artists’ works combines the vocabulary and idioms of contemporary art discourses with the richness of lived experiences. Their images reinforce and extend the artists' sensitivities to history and place, memory and absence, experimentation and conceptual play. They contribute to the development of a new poetics of identity in which the visual, conceptual and political intersect to define wider contexts for contemporary practices.

Together, the Resilience artists negotiate aesthetic spaces through a combination of intelligence and humour, autobiography and historiography, the local and the global. Their works epitomize contemporary Indigenous art practices and individual identities that exist today in the spaces between colonial critique and cultural continuity. These artists inhabit their own territories of existence and resilience that, with critical acuity, they seek to redefine for the future. Ultimately, Resilience is manifested in the large-scale images standing alongside the country's roadways. Resilience is synonymous with these Indigenous women who stand as Defenders of their cultural sovereignty and Protectors of the land.

Lee-Ann Martin

Curator

Lee-Ann Martin is an independent curator of contemporary Indigenous art living in Ottawa, Ontario. She is the former Head Curator of the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina, Saskatchewan and the former Curator of Contemporary Aboriginal Art at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Gatineau, Quebec. Martin’s numerous curatorial projects include the international co-curated exhibition, Close Encounters: The Next 500 Years for Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art in Winnipeg, Manitoba and the nationally touring exhibitions, Bob Boyer: His Life’s Work, for the MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan, Au fil de mes Jours (In My Lifetime) for the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec in Québec City, Québec, and Alex Janvier: His First Thirty Years, 1960-1990 for the Thunder Bay Art Gallery, Thunder Bay, Ontario and INDIGENA: Perspectives of Indigenous Peoples on 500 Years, with Gerald McMaster, for the Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec, which toured internationally. Martin has curated, written and lectured extensively on contemporary Indigenous art both nationally and internationally for more than twenty-five years. Her writing has been published by Oxford University Press, University of Washington Press, Banff Centre Press, National Museum of the American Indian, Douglas & McIntyre, and the National Gallery of Canada, among others.

[i] Janet Silman, Enough is Enough: Aboriginal Women Speak Out (Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press, 1987).

[ii] Bill C-3: Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act. (2010). 1st Reading March 11, 2010. 40th Parliament, 3rd session. Retrieved from the Parliament of Canada website.

[iii] Viviane Gray, "Persistence/Resistance: The National Indigenous Art Collection,” (Ottawa: Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2017). Unpublished manuscript.

[iv] Sherry Farrell Racette, “I Want to Call Their Names in Resistance”: Claiming Space for Indigenous Women in Canadian Art History, Distinguished Women Scholars Lecture, University of Victoria, February 14, 2017, p. 13.

[v] Linda Nochlin, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?," ARTnews (January 1971): 22-39, 67-71.

[vi] Margaret Archuleta, "Why Have There Been No Great Native Women Artists?" Unpublished manuscript, p. 1.

[vii] Michelle LaVallee, ed., 7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. (Regina: MacKenzie Art Gallery, 2014).

[viii] Yamin Jiwani and Mary Lynn Young, “Missing and Murdered Women: Reproducing Marginality in New Discourse,” Canadian Journal of Communication 31 (2006): 895-917.

[ix] Rosalie Favell cited in: Sherry Farrell-Racette, Resilience/Resistance: Métis Art, 1880 - 2011 (Batoche: Batoche National Historic Site, Parks Canada, 2011), 15.

[x] Kathleen Ritter, "The Reclining Figure and Other Provocations,” Rising to the Occasion, (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008), 53.

[xi] Statistics Canada, 2016 Census Program, (accessed 10/25/2017).

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Artist’s statement.

[xiv] Artist’s statement.

[xv] Artist’s statement.

[xvi] The Alpine Club of Canada, The A.O. Wheeler Hut.

[xvii] "Shuvinai Ashoona," Art Canada Institute/Institut de l'art canadien.

[xviii] Heather Igloliorte, "Annie Pootoogook: 1969-2016,” Canadian Art (September 27, 2016).

[xix] The Kino-nda-niimi Collective, Idle No More: The Winter We Danced (Winnipeg: ARP Books, 2014), 21-22.

[xx] Indian Country Today, "Onaman Collective Puts Art Into Resistance," May 1, 2017.

[xxi] “Chinook Jargon is a trade language that was used extensively in the nineteenth century and first part of the twentieth century for communication between Europeans and First Nations people in much of the Pacific Northwest, including British Columbia. Chinook Jargon should not be confused with Chinook, which is the native language, now extinct, of the Chinook people, whose traditional territory is around the lower reaches of the Columbia River, near Portland, Oregon. Although many Chinook Jargon words come from Chinook, the real Chinook language is quite different from Chinook Jargon.” Yinka Déné Language Institute, The First Nations Languages of British Columbia, “The Individual Languages - Chinook Jargon,” (accessed 11/27/2017).

[xxii] Artist’s statement.

[xxiii] Pamela Sexsmith, "The Healing Gift of the Jingle Dance," Windspeaker 21, no. 5 (2003): 28.

[xxiv] "Family, friends, loved ones gather to honour MMIWG across Canada," CBC News/Indigenous/Families commemorate first official MMIWG day in Manitoba, Oct. 4, 2017.

[xxv] Personal communication with the artist, September 5, 2017.